LE CUL MÉCANIQUE by Moses Langtree

Catalogue essay from the exhibition 04 October — 28 October

2006

Esa Jäske Gallery, Sydney

|

|

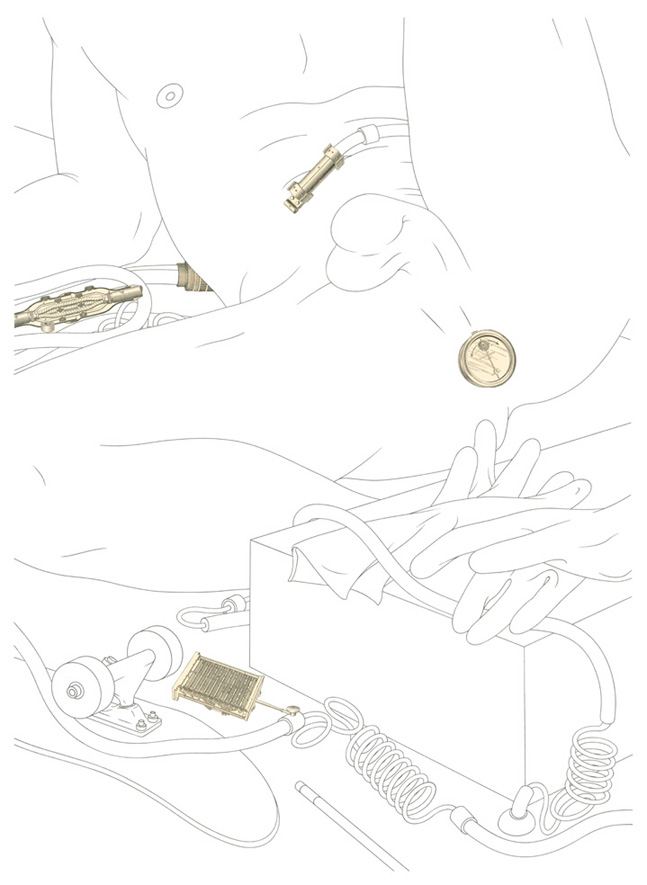

Fallen

Skateboarder (detail)

2006, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no.

MMXXVI |

|

Le

cul mécanique

The mechanical arse

Schranzer’s creative expressions naturally (and convincingly)

convolve and oscillate. His subjects weave and intertwine, or

sit at opposite ends of a room; his various protagonists and personae

gain episodic or periodic favour. Formal appearances fluctuate

as a minimal, abstract aesthetic seeks voice alongside semi-figurations,

or as we find in Le cul mécanique, his more figurative

impulses. Yet, in whatever formal, material or technical way his

drawings, collages, paintings, or objects present themselves,

whichever play, turn or bent of mind directs them, they are, undoubtedly,

united by constant themes — from the esoteric to the sexual

— and by an individual, reduced and linear style. Indeed,

evident over many years is his signature use of an 'industrial'

line and form; a way with and a reliance on

line and edge that preferences the ‘clean and clear’

over a painterly, expressive approach.

In Le cul mécanique the viewer is presented with

a reduced yet figurative modality, and as Schranzer’s focus

is the male body — not culturally and politically allegorised,

but personally and sexually charged — it does beg the question

of its appropriateness; whether his ascetic style linked to the

vernacular of architectural drawing is counter-expressive, and

what its purpose and meaning might be. Where the erotic drawings

of artists such as Jean Cocteau and Jean Boullet are rich in freehand

elements, nuance, ‘sensuality’ and ‘candour’

of line, Schranzer never loses his controlling interest in where

a line leads and when it stops, and rarely allows the line to

deviate in weight and emphasis, limiting its emotive and expressive

potential. There is, in stark contrast to Cocteau’s or Boullet’s

drawings, no sense of warm flesh, raw meat, hot semen, or romantic

sexual possibility: no bedfellow invoked.

In William Burroughs’ Soft Machine one reads of

“street boys… [with] smiles and translucent amber

flesh, aromatic jasmine excrement, pubic hairs that cut needles

of pleasure…” and “asshole[s] fluttering like

a vibrator,” but no such street boys are to be found in

Schranzer’s work. There is eye-candy and there are arse-holes

to be sure, but Schranzer’s young men don’t speak

of a Dionysian spirit, an organic fecundity; rather, on appearance

they are relatively ‘cool’ — removed, largely

travertine-fleshed, oiled, machined — despite what pleasures

they seem to offer. Again quoting Burroughs: “So the boy

is rebuilt [I’ll add, with a mechanical arse] and

gives me the eye and there he is again walking around some day

later across the street and ‘no dice’ flickered across

his face….”(1) Georges Bataille’s phrase also

comes to mind, that “naturally, love’s the most distant

possibility.”(2) Such a ‘detached’ line is surely

an invocation of a lack of interaction; a physical detachment

between the object of desire and the artist, or subject with viewer.

From this we can at least opine that — through his line

work and aesthetic frameworks — Schranzer is not attempting

to primarily arouse the ‘senses’, despite his naked

subjects! We might divine that his youths are not simply sexual

conduits and — in the light of their mechanical arses —

sexual apertures, but psychological channels; or, returning to

our opening line, that there are oscillations present,

even an ambiguity between the psychological and sexual.

|

Fallen Skateboarder (detail)

2006, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no. MMXXVIII

|

º º º

º º º

|

|

As

we begin to touch upon the anus (!) and the body, it might do well

to interject and reflect on the way these drawings principally align

themselves with Western and Eastern erotic art in a fashion that

is not historically or contemporarily outré.

They are mediated and given context by the visible (and sometimes

invisible) traditions of both ‘sanctioned’ high culture

erotica and underground graphics, yet they can still cause shock

or ‘unease’ amongst a presumably informed, Twenty-first

Century audience.

It is insightful, and an indictment, that as a dominant culture

we still have few (or misaligned) entry points into works such as

Schranzer’s, or consciously choose to marginalize it; ask

that drawings such as these remain in the cabinet, the ghetto, or

the gallery that caters to the interests of those homo-erotically

inclined. Courbet’s woman in The Origin of the World

— explicitly posed and strong in sexuality — might cause

some embarrassment (the American tourist, flush-faced, shifting

uneasily from one foot to the other), but it is acceptable within

the erotic paradigms established by and for the male viewer and

most curators (on this subject there are analyses by feminists,

and insights by contemporary writers like Thomas Waugh on the erotic

gay visual subculture and its relationship to sexual and cultural

hegemonies). The decidedly fetishistic scene of a woman ‘strumming’

a young girl in Balthus’ painting The Guitar Lesson

of 1934 can also be made sense of and receives acceptance within

this sexual-politic of the gallery. This extends to the sensual,

mythological, theatrical or comic idioms of Picasso’s erotic

etchings and drawings, for — however on the brink of or indulging

in fornication or relaxedly post-coital his figures are —

they are heterosexual, conventionally masculine, male-centred imaginings

that don’t challenge the sexual orthodoxy.

A toy car shines its headlights onto the genitals of a hollow-eyed

girl in I was a little surprised to observe the mid-wife drive

up in a hot-rod, a 2002 drawing by Del Kathryn Barton, friend

and contemporary of Schranzer. Barton is also faced with some of

Schranzer’s challenges. Though she acknowledges the sexual

element of her artworks and their titillative potential, how does

she 'convince' some viewers that her drawings are not risqué-

or explicit-for-their-own-sake; not mere 'fantasies' giving the

public a sanctioned voyeuristic adventure; that her works do

move beyond the semiotics of ‘rather weird’ Playboy

illustrations (I mention the latter as Barton's nudes have a kinship

to Egon Schiele's emaciated, awkward, sometimes psychotic figures,

though at her more romantic and florid they evoke the sensual androgyny

of Mel Odom's illustrations for Penguin Books, and Playboy

and Blueboy magazines — straight and gay respectively

— that are referential to the Art Nouveau, and late C19th

Pre-Raphaelite and Symbolist and Decadent paintings). How does she

express to 'the few' or to the many that the drawings are autobiographical

and offer visual ruminations on ‘self’; explorations

that assist her to make sense of her ‘journey’, her

deep (and as it is for many of us a questioning and sometimes problematic)

connection to the physical world and all its modern paradigms, nature,

humanity, and spirituality. In her favour, beyond the aesthetic

and stylistic merits of the works, her subjects are female, and

the broader societal and gallery concord we have alluded to permits

them legitimacy; frames them sexually and artistically. In contrast,

if Schranzer’s more sexual drawings suffer under the public

gaze, it is not because they lack meaning, style, or beauty, but

that they suffer from phobias about male-to-male sexual expression

and objectification, or in the case of these specific drawings,

the depiction of the anus. Both still threaten social convention. |

|

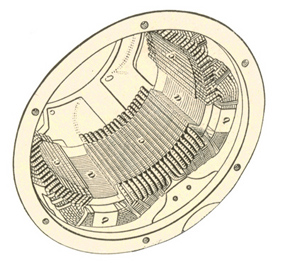

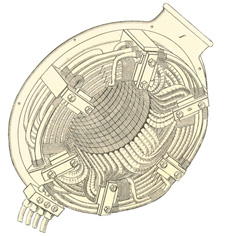

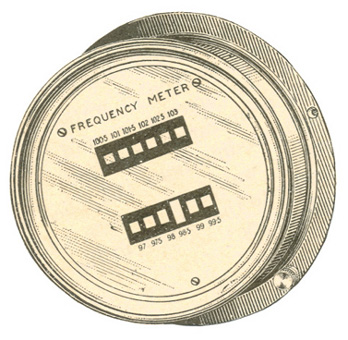

This

said, these anuses are far removed from the realism of pornography

or scientific illustrations. They are collaged sections from mechanical,

not sexual or medical treatises. In many regards they are inventions,

caricatures of, or embellishments on the anus — sometimes

whimsical (a ‘shunt-series’ anus or a meter measuring

‘frequency’) and at their most sexually provocative,

über-anuses far removed from any daily function: so why the

anxiety or embarrassment around these representations? They are,

after all, just one of many elements and signifiers within Schranzer’s

work, and like Barton’s, the drawings have a great authenticity

in the way they speak of ‘self’ — the physical

and the psychic — the ‘other’ — and of broader

human conditions (we will return to the subject of authenticity

later). Like those gathered under the banner of ‘Transgressive

Fiction’ — Georges Bataille, Charles Bukowski, William

Burroughs, et cetera, though admittedly with none of the emphasis

on violence, drugs, religion and politics that can be attached to

the genre — both Barton and Schranzer use the body as a vehicle

for gaining knowledge; searching for self-identity, inner peace,

‘freedom’ and resolution.

|

Skateboarder

(detail)

2006, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no. MMXV |

º º º

º º º

|

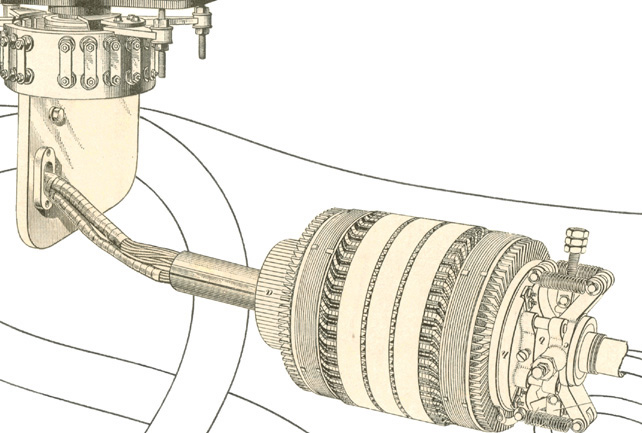

| In

conversation with Schranzer, it was established that many of the

studies for these drawings began their life in Sydney in 2003, before

a move interstate. This in itself might not warrant a mention, but

his relocation to the Gold Coast gives a context and currency to

these works. The fashion (well entrenched before Versace’s

provocative advertising of its low riding jeans) is for youths —

particularly surfers, skateboarders, and labourers — to wear

their pants without underwear, carefully whilst ‘carelessly’

low, half down the buttocks and just above the penis. This has been

jokingly referred to as the P&C, the ‘pubes and crack’

look! It is a sexually charged and socially transgressive act that

inspires few complaints from those with a voyeuristic predisposition,

but even for those without such tendencies it is nigh impossible

to halt the passage of the eye from the iliac line or the navel

down to the pubis! With such a high degree of exposure, they might

as well be surfing, skateboarding, or walking the streets and beaches

naked. The fashion suggests sexual confidence and availability,

but there is an accompanying coolness and self-awareness, meaning

these youths are unlikely to deliver up anything beyond their precociousness

and bravado.

If contemporary skateboarders, surfers, and athletes are icons of

youthfulness, idealism and faultless body development, it comes

as no surprise that Schranzer’s figures make reference to

classical sculptures, from the striding or steadfastly planted colossus,

to the semi-reclining or slain warrior. In many regards, a reference

to the Fallen Warrior (East pediment of the Temple of Aphaia)

is quite appropriate, for as the soldier has valiantly battled and

fallen against a foe, so has the skateboarder battled to perfect

a new trick or jump and in the process landed arse-up or on all

fours; a ‘toppled’ hero of sorts. Classical sculptures

are venerable, ideal, yet usually broken — missing heads,

arms, hands, and feet — and as so many Gods, Immortals, Satyrs,

Lapiths and Centaurs have found, their fate of being sans penis

unites them (Dionysus from the east pediment of the Parthenon,

Apollo on the west pediment of the Temple of Zeus, Praxiteles’

sculpture of Hermes). Schranzer’s youths also suffer

from amputations, or their exposed buttocks and pendulous scrotums

are displayed without sight of their penises. The erotic parts are

mechanical or absent, and any sexual readiness and heroic prowess

is slightly countered or refigured.

In respect of this, it is worth noting that in Schranzer’s

1997 publication Dichter-Zeichner his subjects are often

described as either ‘functioning’ or ‘maimed’,

enabled or disabled: “Ships float calmly out to sea, or are

beached or sunk,” and “sexual youths confront alter-images

of the malformed and sexually dysfunctional.”(3) So we can

recognize these skateboarders, machinists, athletes, and cyclists

in Le cul mécanique as handsome sexual archetypes,

athletic provocateurs, and ‘differently-figured’

transgressive outsiders. We also sense in them metaphors for Freudian

displacement, transference, introjection, and sublimation. They

have psychoanalytical and psychosexual dimensions. |

Cyclist with a Wheel-Repair-Kit

(detail)

2006, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no. MMXXIV |

º º º

º º º

|

But his asshole

sucked me right in…(4)

Alongside gloves, meters,

probes, pumps, springs, and ambiguous apparatus — inserted

or imminently so — are the anuses themselves. Quite the

novel invention, they might calculate, click over, whir and bop,

and occasionally take the form of plugs or stoppers. Certainly,

in aperture form, they not only give a fresh perspective on the

term sphincter but, as working and playing pieces of technology,

they have the pulling power to draw through, the capacity to shut

down, clamp around, dismember, grind, pulp, or extrude. This raises

many questions about the safety of inserting a finger or penis,

and despite the romanticising and fetishizing, they remain

in Schranzer’s works unknowns: pleasure centres

or danger centres; ‘sex-buddies’ who can be trusted

or Loreleis who lure men (literally) to their final end.

|

|

It might be tempting to tease out this pleasure/danger paradigm

and suggest a metaphoric relationship to our current viral world

and appropriate sexual behaviour and its consequences; however,

I cannot imagine this as part of Schranzer’s moral or psychological

scheme. It is more in keeping that these anuses represent his usual

polarities: the erotically fleshed versus the macabre and mechanical,

the working and the redundant, the functional and dysfunctional,

the nurturer or maimer, the loved and the unlovable. As the arses

and other objects are sourced from industrial treatises one hundred

years old (“books covering electrostatics and electrochemistry;

…generators and motors; railway construction and equipment;

steam-, gas-, and water-powered electric plants; telegraphy and

telephony; transformers, converters…”(5)) this position

is strengthened, for in their very ‘existence’ and appropriation

they are presented to Schranzer as precious utilities and resources

or as antiquated and obsolete representations.

Collage is a useful media for Schranzer as there are potential shifts,

ambiguities, and changes in polarity and meaning when source material

is transposed. He has said: “There is… beauty in the

characteristics and metaphysical qualities that are inherent in

these elements… which are not operational within the source

material while still in book form,” and that “elements

are disassociated from their original contexts to give… overtones

of original meaning” or a complete “displacement of

meaning, semantic transformation.”(6) It is obvious this shift

occurs in his representations of the anus: what were once machine

parts for engineer and plant speak of a new kind of sexual industry,

performance, and function.

|

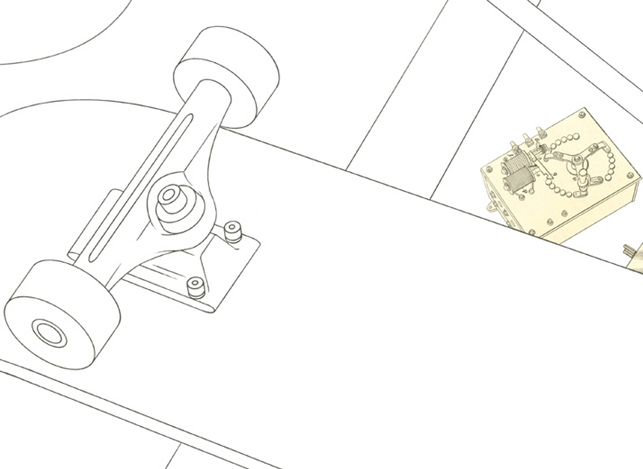

Two Skateboarders (The Crooked Truck)

(detail)

2006, ink and collage on paper, 56 x 76 cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with

title, date, catalogue no. MMXXII |

Max

Ernst expressed the sentiment that collage created "an electric

or erotic tension” by bringing into mutual proximity elements

that were foreign and unrelated, and that “discharges, high-tension

currents would result. And the more unexpected the elements brought

together, the more surprising… the spark of poetry that jumps

the gap.”(7) The use of mechanical parts for anuses (marrying

‘machine technology’ with flesh) and creating occasional

conglomerate sexual props (from unrelated ‘mundane’

parts) brings such erotic tensions. It is the choice of elements,

how and where they are placed and mixed, and what they newly assume

and signify that transforms the poetic and ‘electric’

function. |

|

º º º

º º º

|

| As

Schranzer’s youths blur the line between flesh and machine

they present to us as possible boy-automata. The concept

of an automaton whose actions are, by definition, repetitive and

routine — showing few emotions and performing without thought

— again elicits questions on the character and capacity of

these invented youths. In Young Skateboarder, the protagonist

with his one leg raised might well be caught in a private, playful,

and unselfconscious moment, but he might equally be assuming the

conscious (and oft repeated) sexual pose of the peep-show performer,

automatically waiting to be showered with silver dollars. His exposed

wares come, according to taste, with a fast or slow function!

Does sexual self-awareness and confidence lead to a deliberate stance

or attitude; does it lead to ‘repetitive’, even banal,

exhibitionism? Does a mechanical arse imply emotionless sexual appetite?

Presented faceless (when facial expression can often be a key to

decipherment), our Young Skateboarder’s unpretentious

romanticism, or his seasoned, conceited, narcissistic, even contemptuous

attitudes are difficult to establish. Having earlier discussed the

‘coolness’ of Schranzer’s line work and the implication

for his figures, this last reading could well be accurate —

that his youths are detached, knowing, and impersonal — but

there is still some ‘grey’ in the way that Schranzer

represents, and perhaps we, and he himself, cannot fully

establish whether or when they are warm or cool, hot or cold. |

Young Skateboarder

2006, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no. MMXIX

|

| The

surrealists were fascinated with automata because of the animate/inanimate

conundrum, and the ‘slip’ between the perverse and the

banal. The theme was well developed in Hans Bellmer’s photographs

of assembled mannequins, and a brief look at his work can establish

some differences, confluences, and possibly locate, from a Freudian

perspective, the genesis of Schranzer’s men.

In Bellmer’s photographs his dolls are female and figured

as a “skeletal automaton, a coy adolescent, or an abject pile

of discombobulated parts.”(8) They are variable material amalgamations,

complex and often disturbing. His drawings (for example, Iridescent

Cephaloped, 1939) also express perverse and sadistic undertones:

‘dolls’ and ‘Lolitas’ are subjected to contortions,

superimpositions and reorganization of their erogenous zones, and

are clearly framed within a world of erotic experimentation —

vaginal, anal, and oral. They are thus presented as hyper-sexualized

if not voracious hybrids, or inert mannequins and dolls in a state

of suspended psychic and physical power. Schranzer’s youths

are post-adolescent, expressed as active, idealized (given their

status as skateboarders and athletes) and retain a humanity of sorts,

in that they have not been the subject of gross distortion and bodily

reorganization; will never be composites in the same astonishing

vein — nor reach those perverse heights — of Bellmer’s

figures. In the parlance of Blade Runner they have a sense

of the ‘replicant’. Even amongst the most feverishly

pitched works of Bellmer, what they share in common is an outsider’s

fetishism; a sense of voyeurism rather than participation. Further,

in both bodies of work there are elements of ambiguity in the degree

and combination of emotional, psychic, and physical function, innocence

and corruption, normality and abnormality.

Sue Taylor speaks of Bellmer's dolls developing out of a “series

of three now legendary events in his personal life,” one of

which was the “reappearance of a beautiful teenage cousin.

…Overwhelmed with nostalgia and impossible longing, Bellmer

acquired from these incidents a need, in his words, ‘to construct

an artificial girl with anatomical possibilities... capable of re-creating

the heights of passion even to inventing new desires’."

Given a change in gender, is a type of longing and nostalgia a conditio

sine qua non for Schranzer’s development of his youths?

Bellmer “imagined little girls engaged in perverse games,

playing doctor in the attic; he meditated… on… ‘the

casual quiver of their pink pleats’; and he despaired ‘that

this pink region,’ like the pleasures of childhood itself

enjoyed in the maternal plenitude of a ‘miraculous garden,’

was forever beyond him.” Are Schranzer’s youths with

their pleasure zones — engaged in sport or playing doctor

(the Cyclist with a Wheel-Repair-Kit) — beyond his

reach, and if in reach, are they truly, wholly available?

Taylor also reminds us in her analysis of Bellmer’s dolls

that the “capacity for displacement and the acceptance of

surrogates, Freud stated, enables individuals to maintain health

in the face of frustration.”(9) Are these drawings then the

result of frustration? Are these youths surrogates? How do the psychosexual

fictions and mythologies converge with the lived reality, and how

do the imaginings and the truths ‘fire’ the art? |

|

º º º

º º º

|

| If

these drawings have an apparent sexual element, it is also clear

they have a strong spatial dimension. This statement is advanced

to remind the viewer that Schranzer’s drawings have many attributes

that make for gainful discussion, though we have largely focused

on the sexual and psychological nature of his work. Of course, space

is not just about formal placement and distance; space is about

psychology.

Schranzer employs an intriguing spatial system — a fusion

of systems — that brings to mind De Chirico’s anomalous

spaces. In his essay, Wieland Schmied suggests that “the pictorial

means that de Chirico employs are all directed towards a single

end: to disconcert, to delude, and unsettle the viewer. He begins

with a space that apparently cannot exist, achieved by reversing

such classical organizational principles as linear perspective in

a disruption of the spatial continuum of Renaissance painting, [using]

several vanishing points within one image…. Often foreground,

middle, and backgrounds are undetermined planes that have remote

relationships with each other; perceivable as a sequence of planes

in depth, but arbitrarily stacked with no connecting space between

them. …Such devices give rise to discontinuity and disequilibrium,

incongruity, and incoherence.”(10) Schranzer looked to De

Chirico’s paintings in the 1980s and 90s, so it not surprising

to find vestiges of influence. Schranzer’s drawings have subtly

conflicting perspectives, made more apparent by trying to marry

the various ‘convergences’ of objects he has sourced

for collage. There are indeterminate spaces between elements in

fore, middle, and distant ground as his linear style does not allow

for atmospheric perspective, and passages left empty — ‘white

space’ — come into spatial play. There are ambiguous

or subtly competing scales of objects.

It is, however, not just the use of contradictory vanishing points,

but also the use of parallel projections (axonometric for instance)

alongside them that creates a degree of incoherence. There are also

Oriental views with a high viewpoint, producing strong diagonals

and flat though slanted ground planes, and there are Degas-like

low viewpoints (worm’s-eye views) that allow the spectator

to voyeuristically take in the body, the buttocks and the anus.

When Schranzer does use a middle-level Albertian view, he still

creates spatial diversions and plays, even if subtle.

Perhaps Canaletto would be disappointed by Schranzer’s artifice

— though all spatial systems are an artifice of sorts —

and an engineer highly critical of an object’s plausibility

and structural integrity, but they are deliberate misrepresentations

that further the metaphors of disquiet and dysfunction. |

º º º

º º º

|

| In

closing, Schranzer’s drawings have an authenticity.

This is not meant as a statement on their originality, though they

do have uniqueness, charisma, and a signature aesthetic

and use of line. They are authentic because Schranzer has the conviction

and trust to explore his personal world in the largeness of

things — to express the sexual and psychological ‘known’,

and the ‘mystery’, to establish a truth, however that

truth might shift, mutate, or blur with fantasy. In this search,

he does not bow to fashion, norms, moral impositions, and the fear

of how others might read, respond, dismiss (or blush and shift feet).

Authentic is creating without an audience in mind. Authentic

is about truth, essence and core. Authentic is not a function

of the ordinary.

Moses Langtree

Hulme, Lancashire, and Sydney 2006

NOTES

1.

William Burroughs, The Soft Machine, Paladin, 1986 London.

2. Georges Bataille, “Alleluia,” Vol. 2, sect. 4, La

Somme Athéologique, Guilty, 1944.

3. Kurt Schranzer, Dichter-Zeichner, exhibition catalogue,

1997 Sydney.

4. William Burroughs, op. cit.

5. Kurt Schranzer, A Gentleman’s Fancies, artist’s

statement, 1999 unpublished.

6. Kurt Schranzer, Ibid.

7. Werner Spies, Max Ernst: Collages, Thames and Hudson,

1986 London.

8. Sue Taylor, Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago:

The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body, Department of

Art History, The University of Chicago http://www.artic.edu/reynolds/essays/taylor.php

9. Sue Taylor, Ibid.

10. Wieland Schmied, “De Chirico, Metaphysical Painting and

the International Avante-garde: Twelve Theses”, in Emily Braun

(ed), Italian Art in the Twentieth Century, Prestel-Verlag,

Munich and Royal Academy of Arts, 1989 London. |

Fallen Skateboarder (detail)

2006, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no. MMXXVIII

|

NOTE: Due to the low resolution of computer screens, the lines

of these drawings will present as slightly pixelated. A 'jagged'

quality will be particularly evident on some diagonals and curves;

fine black ink lines will appear faint and tend towards grey on

screen.

|

| |

|

© Moses Langtree and Kurt Schranzer 2007

|

|