THE HARLEQUIN, THE BOX: CONCEITS OF ALIENATION IN THE

RECENT WORK OF KURT SCHRANZER by Meredith Morse

Article from Out: A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Art, No.1

Spring 1990

|

|

|

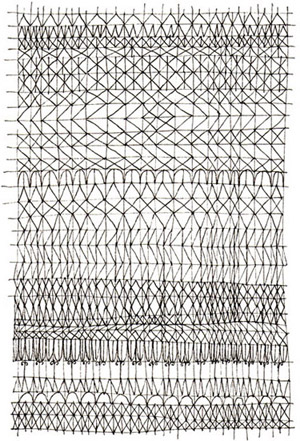

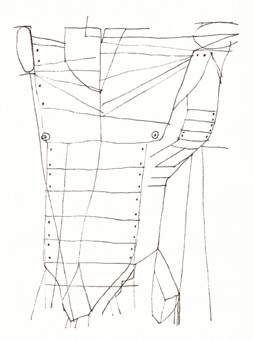

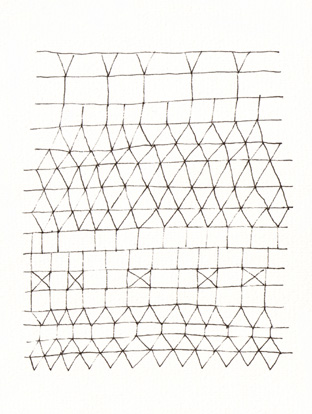

Compressed

Harlequin

1990, pen on paper, 23 x 16.25 cm

Signed and inscribed front with title, date, catalogue no. CMXXV |

|

The

Harlequin The Box

Conceits of Alienation in the Recent

Work of Kurt Schranzer

Kurt Schranzer's recent paintings, on view during July at The

Works Gallery, are small, meticulous still-life and landscape-referenced

tableaux composed of odd objects and geometric and architectural

constructions that structure ironic, open-ended inquiries into

the problematic of an obsessively self-reflective sexual identity.

These works are tiny, precious; they are presented within ornate

escalloped gold and faux-marble frames which situate their object

nature as parodic of bourgeois decorative preferences. A deliberate,

exaggerated 'tastefulness' allows these works to be envisioned

in rich, comfortable surrounds, under their pretext as decoration.

At the same time, their surrealist-informed content undermines

their formal placement. These works function as fetishistic accumulation,

in which libidinally invested forms supplant the more apparently

''neutral'' forms in de Chirico, one of Schranzer's sources of

parody and appropriation. Picasso's surrealist distortions of

the human form, such as the Anatomy series of drawings and the

etching Model and Fantastic Sculpture of the 1930s, in

which body members are substituted for others as well as distorted

and phallicised, provide a closer correlate and model for Schranzer's

organization of form (1). His concern with quizzical sexual and

literary object metaphors overloads their object bearers by hyperfetishing

them: by forcing more readings than the objects can sustain, fetishism

is parodied while at the same time its materiality is indulgently

portrayed.

|

|

|

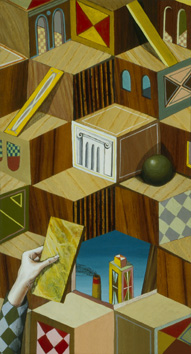

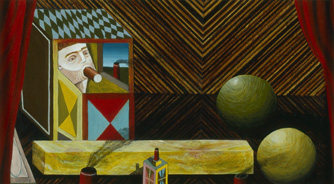

Harlequin,

Metamorphosing

1990, acrylic on wood veneer on panel, 23 x 18 cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no.

DCCCXVII |

Salut

Matelot!

1990, acrylic on canvasboard, 19.2 x 16.4 cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no.

DCCCXXVI |

|

In Harlequin Metamorphosing,

a small still-life of architectural Platonic solids rests upon

a truncated torso-figure which, Archimboldesque, is constructed

almost wholly of collaged cubist and surrealist derived forms.

Flattened checkerboard patterning refers to the Harlequin, whose

hand can be seen inserting a cylindrical penis-form into the composition

over a stylized Picassoid scrotum. Repeated scroll or G-clef shapes,

while referring to the cubist use of musical instruments as subject

matter, can also signify the anus, according to Schranzer. Sets

of curved or straight lines are equally referential to Picasso's

calligraphic shorthand for hair or features in his surrealist-influenced

figurations, as they are to pubic hair, and body hair in general.

A similar clustering of devices occurs in Salut Matelot!,

titled after the French for ''hello sailor,'' as a reference both

to Genet's Querelle of Brest and to the positioning of

the sailor as a male culture stereotype of the sexual. The central

figure, composed of still-life groupings, body parts, and opened-out

box forms, was originally conceived as a suspended mobile, according

to Schranzer. The logic of such an organization, coupled with

Schranzer's appropriation of Picasso's surrealist approach to

the manipulation of the body, dictates an organic, clustered structure

of accumulated parts which is never completed, but can accommodate

new growths, polyps, permutations.

|

|

The

Architect's Failure alludes in title and structure

to an authorial desire for closure, which is never attained.

The hand of the author or architect, and, by implication,

the hand of God, seeks to organize and contain an ordered

landscape of wood veneering and Harlequin motley, which extends

infinitely off the panel in all directions. Yet, a gaping

hole, created by the absence of the pattern itself, punctures

the ordered world (to the surrealists, the world of social

nicety and repression) to reveal a limitless sky and a phallic

smokestack. Within the level of the ordered pattern, only

small doorways are provided as an escape from the relentlessness

of regulation, but they too are devised by the author, which

seeks to cover up the irregularity of the hole to the outside.

From the title of the piece, and in the terms in which the

surrealist project of releasing the unconscious from its Oedipalised

constraints is phrased, the architect (wearing Harlequin motley)

would never conclusively define the subject it attempts to

order.

In its literal shallowness, veneer is used to refer to the

contrast of the fictive, illusionistic space of the painting,

with the decorative actuality of surface: this liberalizes

the nature of repression as masking, parodying the surrealist

project as simplistic. Schranzer's love of surface, whether

as actual veneering or as carefully rendered faux-marble in

painting or frame, contributes self-consciously to a positioning

of the fetishism of order against the chaos of the felt experience

of the fragmented self. But, more than this, his project specifically

investigates the subjectivity of the gendered, male, self,

as it attempts, from a decentred position or range of positions,

to define itself, and to perceive itself in tentative relation

to a love-object. |

The Architect’s Failure

1990, acrylic on wood veneer on panel, (size not recorded) cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no.

DCCCXV |

|

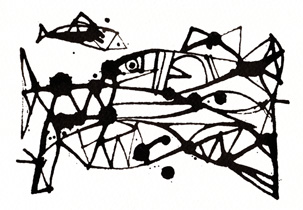

| In his drawings,

Schranzer's use of line is reminiscent of early Warhol (2). It is

arch, deliberately imprecise, and eloquently obsessive. Schranzer's

blotted-line drawings are posed and playful, like Warhol's, though

their serious-but-innocent-treatments borrow style from Klee. His

figurative posings are loose, like Klee's line, but highly self-conscious

as in Cocteau. All pertain (and, as it were, are stripped bare by

the skeletal, definitive line) to the problematic of selfhood: Schranzer's

device of the box-emblem for his self enables him to literally

skirt around the perimeter of this problematic, without attempting

to fix or concretise it. In a sense, these pieces are organized

around open-ended narratives which hint at melancholy tales, romantic

meditations upon love longed for and lost. But the narratives end

at their beginnings: the stage is set, the Harlequin has been given

his lines; but the remainder of the scene is unclear, informed by

a pathos which foresees a sad ending anyway.

|

|

|

Conversation

Between Many Fish

1990, ink on paper, 16.25 x 23 cm

Signed and inscribed front with title, date, catalogue no. CMXV |

Francis Slips

with the Fret-Saw while Sculpting

1990, ink on paper, 16.25 x 23 cm

Signed and inscribed front with title, date, catalogue no. CMXXXVII |

|

|

|

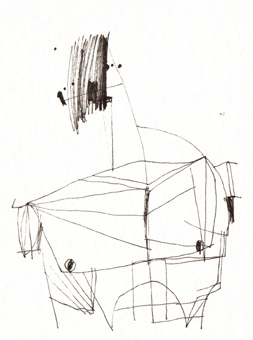

Boy with

Muscles

1990, pen on paper, 18 x 12.7 cm

Signed and inscribed front with title, date, catalogue no. DCCCLXXX |

The Seven

Deadly Sins: Steel-Plated Pride

1990, pen on paper, 18 x 13.3 cm

Signed and inscribed front with title, date, catalogue no. DCCCXXXI |

|

|

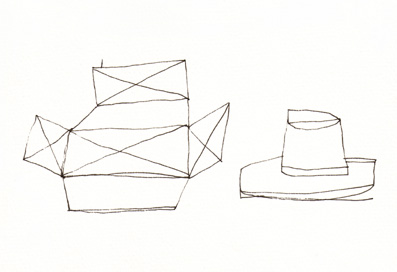

Box

drawings which show a literal opening-out of the box to

signify a receptive opening of the self, such as in Opened

Out Self-Portrait with Francis, posits an equation

of containment with reception: both box-forms and architectural

conceits are devices that function to order, restrict, and

contain, and are thus congruent with signifiers of repression

in the surrealist lexicon: but, as Schranzer's project adds

the nexus of subjectivity/ sexuality/relation-to-another

(which can be seen as the terrain of the sexually marginalised),

these devices make the boxes and architectural forms reinterpretable

as not simply machines for repressive constraint and containment,

but as containers, receptacles, receivers. The prompter

in Still-Life With Prompter's Box is gagged —

filled — with a penis-cylinder which his mouth receives

and which renders him mute. In the love relationships Schranzer's

work speaks of, the partner who receives, who appears to

be acted upon, is caught in flux, without the definitively

demonstrable act of doing to fix his identity: his position

is elusive, changeable: perhaps it is up-speakable, mute.

To call this position ''passive'' is to miss, first of all,

the subtleties of exchange, in favour of the certainty of

a dichotomous structuring which mimics the supposed complementarity

of heterosexual relationships. Secondly, such a position

can be adopted strategically, playfully, or ecstatically:

it does not necessarily or ultimately stand as a subservient

position of humiliation, lack, or even of alienation, though

this last is part of Schranzer’s project. |

Opened

Out Self-Portrait with Francis

1990, pen on paper, 13.3 x 18 cm

Signed and inscribed front with title, date, catalogue no.

DCCCXIX

Still-Life with Prompter’s Box

1990, acrylic on wood veneer on panel, 13.5 x 24.5 cm

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no.

DCCCXXI |

|

Both in his paintings

and drawings, Schranzer offers up colourful, beautifully rendered

image-playthings to distract us from the pain of self-distantiation

and its corollary, self-scrutiny. This examination of the self —

a look at once fascinated, fixated, and pained; oblique, and precise

— speaks of loss and melancholic abandonment. The need to

articulate and fix the self is paralleled closely with the desire

to be hidden, to become an object, a box, or a toy. This dialogue

of the seeking self with itself — or the self with an objectified

other persona which speaks in the guise of a (fragmented) other,

such as the Harlequin, Minotaur, or schizophrene — desires

the establishment of an identifiable integrated self, at the same

time that it denies that this is possible, and seeks to obliterate

the inauthentic self that is posited in the authentic self’s

absence. Ultimately, all that is left is the false and familiar;

the known, fragmented self of everyday knowledge, which, to this

sensibility, preserves enough of prelapsarian perfection and wholeness

to be an intolerable reminder of what one is not, yet which one

longs to be or to love in one's own sex, as in a mirror. |

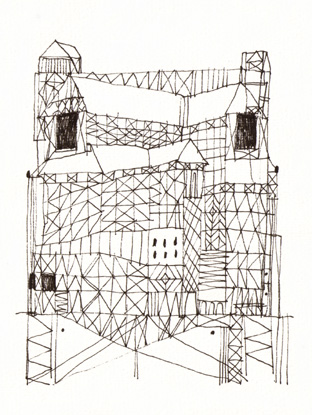

Decapitated

Man as a Greek Temple

1990, ink on paper, 23 x 16.25 cm

Signed and inscribed front with title, date, catalogue no. CMXIX

Harlequin

Disguised as a Tudor House

1990, pen on paper, 18 x 13.3 cm

Signed and inscribed front with title, date, catalogue no. DCCCXXXVIII

Harlequin

in a String-Bag

1990, pen on paper, 18 x 13.3 cm

Signed and inscribed front with title, date, catalogue no. DCCCXXXXIV

|

For

Schranzer the aesthetic ideal, for which the fragmented, imperfect

self yearns is one of a classical purity, an originary unity

and wholesomeness: the boyish, fresh, yet precocious beauty

of the ancient Greek kouros and Roman profile, whose

posture is strong and heroic; whose torso is triangulated,

classicised, as in the photography of Bruce Weber, and that

of Herb Ritts; whose mouth, over a curving jaw, is pouty and

voluptuous. Like the Diskobolos, this figure must

be graceful and lithe; must be mercurially charming and elusive

like Puck; and stylish, fey, yet potent, as are the hommes

fatals of Cocteau's drawings. Though this figure of aesthetic

perfection is integral to Schranzer's conceptualising as a

whole, it can be seen to inform his work most obviously in

terms of its effects upon emblematic structures signifying

Schranzer's self, which are implicitly positioned as its opposite;

and its manifestation in various ''youth'' drawings whose

subject is the sprite-like, palpably erotic presence of this

knowing, precocious boy. Columns and other architectural conceits

of ''the classical'' are used emblematically throughout Schranzer's

paintings and drawings to indicate the pervasiveness of this

aesthetic which functions as a reminder of this idealised

beauty, and as a reproach to the subject, which always falls

short of perfection according to this scheme. A true love-relation,

by this logic, can only exist between idealised equals:

Thus, I began as a romantic idealist, seeking only the

perfect love. I looked for a companion who would be both brother

and lover, who would be a fellow explorer and sufferer, a

playmate to laugh and cavort with, a like-minded philosopher

to muse over humanity’s plight with. (3)

In Querelle of Brest, Lieutenant Seblon keeps a diary

in which he carefully records his most minute observations

of the matelot, Querelle. It is a litany of love, a hymnal

of yearning desire to the grace of Querelle's unthinking,

animal beauty; to the manner in which Querelle so easily and

naturally inhabits his own body. When Querelle meets Gil,

he feels as if he has met a ''minor Querelle'' an ''embryo

Querelle (4), and it is like kissing himself, his equal, when

they embrace. The Lieutenant is a man of duty, of artifice:

he marvels at Querelle because of his own self-consciousness.

He would never be a suitable lover for Querelle in terms of

this narrative of idealised love as mimesis; and indeed, though

Querelle is aware of and exploits the lieutenant's love, it

is never consummated. In fact, non-mimetic love in the narrative

is characterized by the exploitation of a power relation.

It is this inequality of power relations which the subject

in Schranzer's schema fears, in its longing for an authentic

love, and thus an authentic self.

The personae of the Harlequin, and to a lesser extent, the

Minotaur and the schizophrene, operate in Schranzer's work

to elaborate upon the project of the speaking of the fragmented

self. These figures in general conflate to signify the ridiculousness

and monstrosity of a self that must perform at the periphery

of social discourse.

In his Rose period, Picasso combined attributes of the Harlequin,

originally a theatrical figure, with that of the saltimbanque,

a street acrobat, and the jester or fool, the medieval court

figure of entertainment and ridicule. The resultant figure,

sometimes portrayed with Picasso's facial features as in At

the Lapin Agile, served as an alter ego signifying both

his peripheral position in society as an artist, and as a

barometer of his domestic happiness or alienation (5).

Picasso's Minotaur, unlike the terrifying figure of classical

mythology, is a vulnerable figure, a playfully comic grotesque

who, just as he is sexually potent in some representations,

is portrayed as vanquished and wounded in others, his symbolic

castration all the more pathetic because his awe-inspiring

strength. Picasso's inspiration for this alter ego figure

came from his frequent contact with the ritual of the corrida,

or Spanish bullfight (6). In the ring, the bull's natural

strength and courage were used against him, such that the

greater his fight against his fate, the greater would be his

eventual punishment by the toreador, whose role was to ritualistically

exhaust, wound, and kill the bull. According to Gloria Fiero,

Picasso saw himself as in this situation, as a bull-man or

Minotaur (7). In a stage curtain design for Le Quartoze

Juillet, Picasso portrays a limp, vanquished Minotaur,

dressed in Harlequin's motley, slumped in the arms of a muscular,

bird-headed monster. This defeated creature, conflated with

the alienated role of the Harlequin, stands for Schranzer

as a significant embodiment of the separate spheres of alienation

in which the fragmented self moves and finds itself. In an

earlier painting of Schranzer's he renders the Minotaur as

an armless, horned boy. The figure is maimed incomplete, broken.

Clearly, to operate at the periphery of subjectivity, particularly

sexual subjectivity here, is to risk dismemberment: to risk

not only the perception cast upon this subject as incomplete

or grotesque, but a symbolic castration that removes the subject

from membership in the symbolic order. The marginalised subject

perceived thus is not allowed the space in which to speak.

|

|

|

The marginalised

subject, negligibly placed at the fringe of mainstream social exchange,

is thus estranged from himself just as he is excluded from the socius.

The disallowing of a legitimised signifying framework impacts in

several ways. Only mainstream, and therefore dominant, discourses

are couched in terms of transcendental universalisms, characterised

at their normative point of origin by heterosexism as well as other

privileging determinants. All frames considered worthy of evaluation

(and the application of connoisseur-based objectives) must be seen

to occur within the mainstream for criticism, as such, to remain

operative. To step outside this, to make work labelled ''gay art''

is to risk its perception in terms of a categorizing of experience

generated by mainstream tactics of excising otherness from the body

politic. An internalisation of such projections upon the marginalised

can generate work in which stereotypes are investigated in terms

of the problematic of subjectivity. Such a self-reflective project

risks, in mainstream perception, being regarded as kitsch. Thus

''authenticity'' becomes, if the term can be used divorced from

an absolutist context, a measure of the extent to which one can

speak ''marginality'' with the tools at hand — recognizing

its construction as such — and yet still articulate the conditional

truths of felt experience.

Schranzer's work engages with this problematic by perceiving appropriated

forms, conventions, and personae as strategic devices which can

be utilized to establish a range of positions from which to speak

his particular subjective and social disenfranchisement. This usage

should not be considered completely isomorphic with concerns articulated

in the current ''mainstream'' of post-structural art practice, as

it engages as well with an aesthetic of male subjectivity that lies

outside it. What Schranzer's concern for the inner and the outer

of subjectivity indicates in these terms, is a need for interpretive

systems and forums which can accommodate the complex relations among

multiple mainstreams and margins, and provide an alternative

to extant dichotomising models.

NOTES

1. See John Golding's essay, ''Picasso and Surrealism,'' in Roland

Penrose and John Golding (Eds.), Picasso 1881/1973 (London:

Paul Elek Limited, 1973).

2. See Rainer Crone, Andy Warhol: A Picture Show by the Artist

(New York: Rizzoli International Publication, 1987), originally

pub. as Andy Warhol: Das zeichnerische Werk 1942–1975

(Stuttgart: Wurttembergischer Kunstverein, 1976), for a thorough

look at Warhol’s early graphic work.

3. Gary 'Wotherspoon, ''The Loner,'' in Gary Wotherspoon (Ed.) Being

Different (Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1986), p. 117.

4. Jean Genet, Querelle of Brest (London: Paladin Books/Collins

Publishing Group, 1987: first pub. in UK in 1966), p. 205.

5. For a discussion of the iconographic uses of the Harlequin figure

in Picasso, see the following by Theodore Reff: ''Harlequins, Saltimbanques,

Clowns, and Fools,'' Artforum (10:2, Oct 71): and, ''Love

and Death in Picasso's Early Work,'' Artforum (11:9, May

73).

6. See Roland Penrose, ''Beauty and the Monster,'' in Penrose and

Golding, op. cit.: and Gloria K. Fiero, ''Picasso's Minotaur,''

Art International (26:5, Nov 83).

7. Fiero, op. cit. |

|

|

| |

|

© Meredith Morse

1990 & Kurt Schranzer 2007 |

|