NO MAN IS AN ISLAND: REFLECTIONS ON ‘THE GREAT WALLS’

by Kurt Schranzer

Essay for the exhibition 16 April — 19 June 2011

Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest, Penrith NSW

|

|

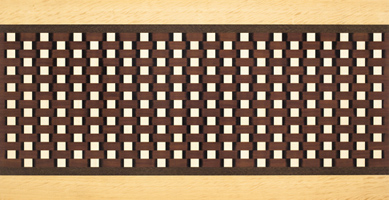

Palace Wall

2008–2010, acid catalysed varnish, wood veneers, medium

density fibreboard, plywood, welded aluminium frame, 210 x

120 x 6 cm

Fabrication with Josef Schranzer

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no.

MMLVII |

|

No

Man is an Island

Reflections on 'The Great Walls'

|

|

No man is an island, entire of itself;

every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.

John Donne (1573-1631)

|

My first studies for The Great Walls found their embryonic

expression in January 2001, so a decade has passed during which

these sketches were elaborated upon, developed into orthographic

drawings and digital drafts, and finally, manufactured. For a creative

context, my initial ideas flowed from the large-scale wall drawings

I was then exhibiting, which were part meditations on the formal

and metaphysical expansion of pictorial space, and the

rejection of the confining influence of the frame. I was intrigued

by the prospect of the gallery wall becoming a principle player

along with the drawing, which might allow for multiple and more

mysterious interpretations of the finite. Predicated on those interests,

The Great Walls has resonances of the projections, flows,

and visual arrestments that then occurred. The final panels and

high-relief wall pieces (in situ) have become windows, views, and

frameworks punctuating architectural space, and trompe-l'œil and

conceptual extensions of it (the relationship, then, is not just

spatial, but metaphoric, symbolic, narratively based).

|

|

The

artworks are also inspired by and derive their meaning, structure,

or content from the architectural element, largely, but not

above all else, the wall — halls, courtyards, pilasters,

coffers, columns, towers, and the like. They are also poetically

conditioned by systems of matching veneer and the material

character of woods — their grains, patterns, and features

governed by growth and cutting method — and, of course,

are technical and material adaptations of intarsia and marquetry

as seen in furniture and, not surprisingly, wall decoration.(1)

In development — as the themes and parameters of the

exhibition became clearer and more layered — it was

evident that the artworks were also the fruit of an association

with my father Josef Schranzer (born 1937, St Paul im Lavanttal,

Austria), a cabinetmaker, and a posthumous association

with Henry Moore, my maternal grandfather (born 1879, Manchester,

England), who was working as an engineer’s patternmaker

as early as 1901. This ‘alignment’ was increasingly

tied to the adoption of forms used by Schranzer and Moore

in their joinery and object making practices, reflecting the

traditions of their trades and their creative attitudes between

the 1940s and 1960s. Moreover, it entailed a physical collaboration

with Josef Schranzer in manufacturing the panels, quite appropriate

as the exhibition progressively floated itself on the converging

currents of self, family, and culture — the ‘passing

on’ of patterns, decorative schemes and standards, creative

forms, languages, and impulses which would thread the historical

and the contemporary, the personal and the collective. So

these associations cum collaboration lay a significant aesthetic,

conceptual, and practical foundation.(2)

Implicit in these flows through history, in those interpretations

and inventions, for instance, of my own father who trained

as a cabinetmaker in the 1950s, through his Tischlermeister,

who was in turn taught by his Master in carpentry, and so

on, are issues of authorship and originality, and the replication

and reinvigoration of both style and tradition. This generational

transmission finds a parallel in the history of Islamic geometric

decoration, with its basic shapes or ‘repeat units’

arranged in different permutations or from which more complicated

patterns were constructed. They were, over time, copied, developed,

transformed, and applied in any number of increasingly complex

(and mathematical) ways to fill and link space, and to increase

variety and visual effects. Intrinsic too, is the notion that

designs may simply become part of a visual and aesthetic identity,

acquired, reordered, and revealed in one’s own art making

through an ‘aesthetic osmosis’ — ergo it

is not so much a question of ‘borrowing’ the extrinsic

but of ‘expressing’ the instinctive. In this sense,

John Donne’s words might well be appropriated for the

creative type; that no man is a creative island, entire

of himself, but a piece of the whole.

Tied to this is the universality of certain motifs, patterns,

and schemes across cultures. However mediated by style, setting,

materials, and technology, these motifs and visual orders

have an elemental and collective resonance. Checkerboard,

diamond, cube, Greek-key and simple repeat patterns extending

to complex tessellations through isometry can be found in

Tribal and Folk Art, Greek Geometric phase pottery, on the

floors of Ancient Roman villas, on the walls and ceilings

of the Alhambra, and within C20th abstract painting. Many

basic forms and patterns are part of (or interpretations of)

the phenomenological world, and this ‘taxonomy’

of forms and arrangements satisfies practical, formal, and

psychological needs (for instance, the recognition and familiarity

of shapes and simple repetitions are a suitable way to hold

a viewer’s attention and allow the eye and mind to roam,

yet be controlled). Further, they can accrue meaning and therefore

play symbolic roles. |

Study

for Star Walls (The Soul's Antechamber)

2007, (detail) pencil on graph paper

|

|

Study

for Star Walls (The Soul's Antechamber)

2007, 2nd digital version

|

|

Work

in progress on Star Walls (The Soul's Antechamber)

Dunheved, NSW, June 2008

Photography: Kurt Schranzer |

In The Great Walls these schemes are clearly evident

— checkerboard, cube patterns, and stars — for

they are very much a part of my father’s traditions,

broader visual traditions, and through exposure, mine. Of

course, it is interesting to note that despite the cultural

importance of certain motifs and geometric patterns, it is

also true they have had greater prominence during certain

periods within a given culture or within certain disciplines

such as architecture and the industrial arts. Oleg Grabar

(in The Mediation of Ornament, six lectures delivered

at the annual A. W. Mellon Lectures in Fine Arts at the National

Gallery of Art in Washington, 1989) writes of geometrically

based patterns being “relegated to a relatively limited

role in Western Painting and Sculpture from the Middle Ages

onward, except for mosaic and other tessellated floors of

Southern Italy and for marquetry and other techniques of applied

and industrial arts….” They only resurface as

a potent expression in the post Cubist world, particularly

in the works of Escher, Mondrian, and hard edge, non-objective

abstraction. |

|

| Exempting

the Islamic world, Grabar largely sees them as being more frequently

associated with “areas of creativity [such as textiles] in

which functional purpose dominates the fashioning of the objects,

where craft predominates over art,” and as the preserve of

“the illiterate, the remote, the popularly pious, …women”

or creative orphans such as Escher who sit uneasily within the “pantheon

of contemporary artists.”

|

| Thankfully,

pollination between disciplines and styles is a given within

the contemporary art world, and there is little argument about

the potency of geometric minimalism and abstraction as expressed

in 20th century and contemporary art. Further, postmodern

art is less embroiled in the ‘class’ association

and snobbery between the High and the Low — to the use

of certain forms and the use of techniques like embroidery,

weaving, knitting, or inlay — which leads me to the

point that I am quite interested in blurring the customs and

grammars of Fine and Applied Arts: my paintings circa 1990

incorporated wood veneers, and my drawings over the last 15

years have used the tools of engineering drawing.

One trusts, of course, that this mix of the technical, decorative,

artistic, and creative, has been well advanced within The

Great Walls. Broken Column, for example, was

developed from Henry Moore’s early 1940s hexagonal and

dodecagonal receptacle for knitting needles, capped (he was

a Freemason) by a pyramid. Translated into a tapering octagonal

prism — a final aesthetic and structural synthesis,

for me, of all these Euclidean prisms and energies —

it is funereal, austere, masculine yet emasculated, in a state

of ‘crossing’ over; sinking into the wall of the

gallery and by implication entering a hidden, alternative,

or higher dimension, perhaps redemptive. It evokes time’s

passage and the connections (both concrete and dissolving)

we have to ancient cultures and architectural relics. Its

awkwardness is also reminiscent of unsettling features within

Mannerist architecture such as Michelangelo’s vestibule

of the Laurentian Library, Florence, where — beyond

the broken pediments, blind niches, and strangely cascading

stairway — the pilasters of the niches taper downward

and the columns sink into the vestibule’s walls. It

is for such an interpretation — for these kinds of allusions

— that I speak of myself (and this exhibition) being

conscious of, and alive to, the architectural element. It

is also obvious how the gallery wall becomes an important

player metaphorically and conceptually: the ‘sinking’

nature of the artwork is only made possible by the wall it

disappears into.

Likewise, the gallery wall is fundamental to the narrative

of Porthole Wall. Logically placed at eye level,

the circular windows recreate the below-deck opportunity for

a much-needed-yet-limited view of the world, and the wall

itself legitimately expresses a boat’s hull and corridor.

Together they hint at the long horizontal lines and nautical

elements of the ‘streamline moderne’ style of

the 1930s. Needless to say, Porthole Wall promises

a contemplative glimpse of a soft horizon and an expanse of

ocean, or, as the artwork (in situ) is in close proximity

to the Nepean River, it may well reflect a diverted channel

— a metaphysical tributary — of it. The frames

for the tondi are copies of those my grandfather Henry Moore

manufactured during the late 1940s, to this day still encasing

reproductions of great Master paintings.(3)

|

Broken Column

2009–2010, acid catalysed varnish, wood veneer,

plywood, aluminium channel

Installed dimensions 218 x 100 x 31 cm

Object dimensions 210 x 62 x 31 cm

Fabrication with Josef Schranzer

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date,

catalogue no. MMLIV |

|

Porthole Wall

Porthole Wall

2009–2010, acid catalysed varnish, wood, wood veneer, medium

density fibreboard

6 units, each unit 19 Ø x 3 cm, installed dimensions variable.

Fabrication with Josef Schranzer and Darren Clark

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no. MMLXV |

|

Left:

Thatched Tower

2007–2010/2015, acid catalysed varnish, burned matches, wood

putty, wood veneer, plywood, welded aluminium frame, 215 x

64.5 x 22 cm

Fabrication with Josef Schranzer

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no.

MMLXI |

|

Various essences are at play in Thatched Tower, which

was constructed with over 28,000 burnt matches. Aesthetically

it is modernist, materially it evokes the medieval, structurally

its monolithic quality aligns itself to ancient architectural

posts and the heavy upright stones of megalithic portal graves,

even Romanesque towers. Not impossibly, it is a cross without

its crossbar.(4) Early crosses in swastika-form may well have

been a representation of sticks used to kindle fire, so coincident

with my use of matches, the artwork has become a symbol of

the burning pyre and cross, and within its flames, the heretic

at death. Associatively, it toys with the word faggot,

pejorative slang for homosexuals and the bundle of sticks

or branches tied together and used for fuel. Fire and faggot,

the punishment of the outsider and heretic! The use of matches

and checkerboard pattern is drawn from a corner table built

circa 1967 by Josef Schranzer.

Thatched Tower, therefore, makes numerous historical

and architectural references and clearly appropriates patterned

schemes that my father has used, but it also pointedly engages

with ‘the personal’, enmeshing to greater or lesser

degrees — and, for any of these artworks, according

to expressive need — the political, the humanistic,

the sexual, and the spiritual or esoteric. This conjunction

is evident in Star Walls (The Soul's Antechamber),

where the panel functions as a window into a small room, an

antechamber, with four stars. Again, this work draws upon

the familial: cabinets made by my father, their doors having

star designs which for Alice in her looking glass might well

open to new worlds. Of course, these stars have their own

long history, adapted from the mariner’s rose compass

and old maps, finding their way into quilting, marquetry and

inlay practices. Yet, the panel is more than this sum: it

alludes to a text I have often interpreted from the Egyptian

Book of the Dead: “I am a child of earth and of

starry heaven, but my race is of heaven alone.” It is

a little window into a stellar soul. My stellar soul.

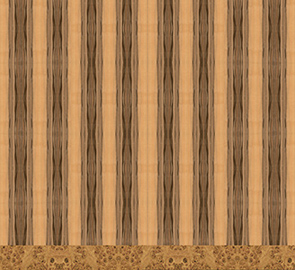

The double-panelled Forest Wall, Bavaria (for the Brothers

Grimm) constitutes a place of rather nightmarish proportions;

trees anthropomorphized into a blockade of ominous sentinels.

It uses the metaphor of the wall for its expressive power.

I am reminded of Leonardo’s proposition that “it

should not be hard for you to stop sometimes and look into

the stains of walls, or ashes of a fire, or clouds…

in which... you may find really marvellous ideas,” an

activity synonymous with my childhood history and visualizations.

The character and beauty of wood speaks for itself and the

panels are allowed to develop that ‘marvellous idea’

into life; the trees transform into the distorted skulls of

horses or antelopes, and their strong nasal cavities soon

become the vulvae of shrieking harpies.

|

|

| |

Forest

Wall, Bavaria (For the Brothers Grimm)

2008–2010/2015, acid catalysed varnish, wood veneers, medium

density fibreboard, plywood, welded aluminium frame

2 panels 220 x 120 x 6 cm, overall dimensions 220 x 240 x 6 cm.

Fabrication with Josef Schranzer

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no. MMLV

Above right:

Forest Wall, Persia

2008–2010/2015, acid catalysed varnish, wood veneers, medium

density fibreboard, plywood, welded aluminium frame

220 x 120 x 6 cm. Fabrication with Josef Schranzer

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no. MMLVI

|

Simple in design, but complexly fusing themes of culture, history,

place, and the architectonic, Forest Wall, Persia makes

reference to the land of Iran though more broadly alludes to Mesopotamia,

the ‘land between the rivers’ (Tigris and Euphrates)

corresponding to Iraq, parts of Syria, Turkey and Iran. It evokes

palm trees, the cane-breaks of the marshlands, and forest-rivers

and floodplains. It also suggests palaces set in walled gardens,

since the Babylonians and Assyrians planted fruit trees in their

courtyards and temples to recreate the concept of paradeisos,

Paradise and the Garden of Eden. It calls to mind the famed hanging

gardens constructed not at Babylon, but at Nineveh by the Assyrian

king Sennacherib. I am mindful of the Babylonian and Assyrian

sacred tree, and semi-engaged columns imitating the trunks of

date palms, the columned palaces at Persepolis, Nimrud, Khorsabad,

and Nineveh; especially Nebuchadnezzar’s throne room façade

(restored and housed in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum) with its

four tiled palm trees.

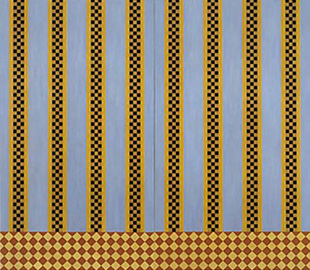

Reflecting on the ancient Chaldæan art of enamelling on

bricks and tiles carried on by the Susians, Persians, and Babylonians

— the great Palace of Darius at Susa with its tiled lion

friezes, winged sphinxes, and rows of archers, and Nebuchadnezzar’s

Ishtar Gate and Processional Way — Processional Wall

can be interpreted as a re-presentation or homage to such decorative

architecture. Yet, without its splendor — stripped of its

bas-relief elements, with an austerity and melancholy pervading

the artwork — it is also in keeping with the awkward spatial

projections and the ‘stillness’ of both Italian mid-15th

century Annunciation painting and 20th century Metaphysical painting.

Secret Window also announces historical debts to the

staged and stilted spaces of Proto and Early Renaissance painting

(Duccio, Monaco, di Paolo, Giotto, and later Uccello). Through

a window, the checkerboard path of a hortus conclusus,

an enclosed garden, is tilted upright in a nod to 20th century

abstraction, and beyond the courtyard, the grain of walnut veneer

(upper-right) suggests a row of Cypress, Poplar, or Pine trees,

the latter common in the background of Madonna paintings. It is

a mannered amalgam, the artwork advancing and intruding into physical

space while its projective illusionism leads our eye into pictorial

space. Palace Wall is another busily patterned work that

references interior spaces and courtyard enclosures, whilst The

Great Hall, Egypt is a more stern, unadorned architectural

description whose columns and wall — reminiscent of peristyle

courts and hypostyle halls — plays a subtle game, shifting

between salient and recessive positions.

|

|

|

| Processional

Wall

2008–2010, acid catalysed varnish, wood veneers, medium

density fibreboard, plywood, welded aluminium frame, 2 panels

220 x 120 x 6 cm, overall dimensions 220 x 240 x 6 cm. Fabrication

with Josef Schranzer

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue

no. MMLVIII

Right:

Secret Window

2009–2010, acid catalysed varnish, wood veneers, medium

density fibreboard, plywood, welded aluminium frame, 210

x 90 x 25 cm.

Fabrication with Josef Schranzer

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue

no. MMLIX

|

|

Woven

Wall (alongside Broken Column and Thatched Tower)

is one of the more reductive and abstract artworks on exhibition,

relying on a simple geometric repeat pattern based on woven baskets,

yet it too might be read as part of an edifice, an interpretation,

perhaps, of the glazed tiles and brick patterns of Mesopotamian

architecture. The repeat configuration (also adopted in

an early painting The

Alchemist, 1992) draws upon a circa 1960 jewelry

box made by my father. Its technique of scorching or burning veneer

with hot sand (to shade or suggest roundness) is an established

process going back to the 15th and 16th centuries. This technique

was also exploited in Window to the Universe, with its

pulsating stars and gridded and woven pathways constituting, perhaps,

some new hypothesis or explanation or offshoot of mathematics and

quantum super-string theory, contrasted with its burl walnut heart

articulating the unfathomable mysteries and nebulous nature of the

universe. Does it only question, or does it posit and mirror theoretical,

natural and esoteric laws, expressed in symbols and geometry?

|

Woven

Wall

2008–2010, acid catalysed varnish, wood veneers, burned

wood veneer, watercolour,

medium density fibreboard, plywood, welded aluminium frame,

120 x 235 x 6 cm

Fabrication with Josef Schranzer

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no.

MMLXIV

|

As

abstract investigations these latter works search for many

syntheses, and ideally aim to be revelatory of the archetypal,

and the deep and fundamental, sublime nature of things: Window

to the Universe, for instance, seeks to express the universe’s

connective threads; it’s fabric. Quoting art historian

Charlotte Douglas (Pamela Schaeffer, ‘Spirituality in

Art’ in Christian Century, 1987), such abstract

language has been prompted by a need for new dimensions of

consciousness, suited to “‘serve as a passport

to and report from’ the so-called higher realms.”

Intrinsically, it is linked to the desire for a universal

metaphysical lexis and, if we borrow a term from Schwaller

de Lubicz,(5) Window to the Universe attempts to

express "symbolique" or the "Language of the

Gods," using symbols as letters in an alphabet that makes

sense of both scientific and esoteric realms; reflecting spirit

manifesting into matter and their harmonic relationships,

underpinned by the pandeist’s belief that the Universe

as God took physical form in order to experience

the being and the play between the elements of the universe

(that is, itself).

As part of that abstract language, these panels build upon

a visual and conceptual base evolved in earlier wall drawings,

as well as painted and pencilled artworks from The Great

Library series (circa 2000), which developed from collaborative

drawings made with the artist Joe Frost (b. Sydney 1974),

who in turn had drawn inspiration from Agnes Martin’s

abstract drawings and paintings. Some of these panels also

hold resonances with the work of Andrew Christofides (b. Cyprus

1946), a contemporary and colleague. I make note of these

facts to further illuminate the connective threads that operate

between artists, or generations, within and across various

traditions.

|

Window

to the Universe

2008–2010/2015, acid catalysed varnish, wood veneers, burned

wood veneers, watercolour,

medium density fibreboard, plywood, welded aluminium frame,

120 x 235 x 6 cm

Fabrication with Josef Schranzer

Signed and inscribed reverse with title, date, catalogue no.

MMLXIII

|

|

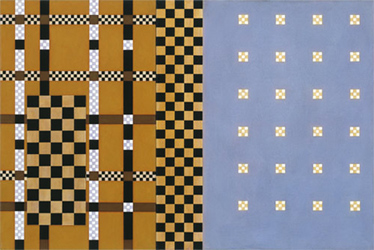

| In

the case of Christofides, it is no surprise that patterns

and compositional devices within Window to the Universe,

and segments of Palace Wall, strike visual chords

with his paintings. In An Interview with Artist Andrew

Christofides (2008, geoform.net), Christofides speaks

of his works having links to the Italian Renaissance and “the

early European utopian movements — Suprematism, De Stijl,

Constructivism,” though his geometric sources are enmeshed

quite broadly, “initially [arising] out of [his] game

sequence paintings of the mid 70s,” an early empathy

with Paul Klee’s paintings of “irregular checkered

patterns of color”,(6) later of antique maps, and more

recently the “gridded excavations of ancient architectural

foundations” and icon painting. Over the years, and

through many subtle transitions, his work has always retained

the significant motifs of the checker and grid, which are

also elemental patterns found in weaving, marquetry, mosaic,

and architecture. It is true to say that for both of us, checkers,

grids, and basic repeat patterns have been passed through

personal and cultural filters, and (whether major or intermittently

used motifs) have become our own.

|

Andrew

Christofides, Echoes, 2006

acrylic on canvas, 40.5 x 60.5 cm

|

|

It

is interesting to note that as I was mindful of his paintings when

constructing Window to the Universe and Palace Wall,

Christofides was to make use of the composition from the digital

study for Forest Wall, adapting it to his usual geometric

abstractions in Study for Pantheon: after Kurt, and Pantheon:

after Kurt I and II, produced in 2007 and 2008. These

kinds of pollinations are a wonderful tribute to art and visual

form and the subconscious or seminally conscious transmissions that

can occur; communicating the visual pull and hold that ‘things’,

‘objects’, and ‘designs’ can have; reminding

us of the expressive, compositional, stylistic and aesthetic continuities

between family generations, artists, genres, and applied and fine

art traditions. I use the analogy that artists and their creative

trajectories are part of a cloth that is woven, knitted, embroidered,

even complexly knotted. It is romantic and indulgent to think of

our selves in a vacuum — as creative orphans or geniuses —

beyond the forces of evolution, untouched by voices that, in a sense,

are ours already. No man is an island.

|

Study

for Forest Wall, 2007, digital study

|

Andrew

Christofides, Pantheon: after Kurt II, 2008

acrylic on canvas, 213 x 244 cm |

|

Though I take Philip Guston’s words out of context in his

dialogue with Harold Rosenberg (Philip Guston’s Object,

a Dialogue, 1966 interview), his statement is a fitting address

to these confluences, influences and the development of forms: “It

has to be new and old at the same time, as if that image has been

in you for a long time but you’ve never seen it before. When

it comes out, [you] must have this double experience in yourself.

I can’t accept something which is so new that there’s

no recognition of myself in it.” In all this absorbing and

reconstituting, there is a sense of taking and making something

old, something new… slipping on a coat owned by many

that sits beautifully, comfortably, uniquely moulded, at one with

the self.

Kurt Schranzer

March 2011

NOTES

1. Marquetry, inlay, and intarsia have been used to embellish walls,

furniture, boxes, reliquaries and ceremonial regalia. Their traditions

go back to ancient Egypt, Rome, and Persia, finding strong expression

in 13th–16th century Italy and Germany. Examples might emphasise

vegetal, zoomorphic, abstract and geometric schemes, or showcase

complex pictorial and perspectival effects. Intarsia and marquetry

are similar. The technique of intarsia — derived from the

Latin interserere “to insert” — inlays

selected pieces of wood (or ivory, metal) within a solid matrix,

or more often, by individually cutting, shaping, and sanding separate

pieces of wood and fitting them together on a surface like a jigsaw.

By contrast, marquetry is the gluing of a pattern of thin veneers

upon the wood carcass.

2. Suffice it to say, working together with my father has time and

again elicited the question “What is it about fathers and

sons?” as if the undertaking has been one of romantic and

symbolic reconciliation and reconnection — an unfolding story

about prodigal and penitent sons. This thinking underestimates the

complexity of my intent.

3. A tondo (plural tondi) is a circular painting or relief, and

is often used to describe the circular representations of Madonna

and Child that are characteristic of the Florentine school from

the mid–15th to the early 16th century.

4. Crosses may have a single or double crossbar, in numerous stylistic

and structural variations, for example the Tau cross, St Peter’s

cross, the Lorraine cross, and the Greek cross. The artist can easily

adopt, adapt, or create an entirely new ideograph without prior

convention to meet personal and symbolic needs.

5. René Adolphe Schwaller de Lubicz (1887–1961) spent

15 years studying the art and architecture of Egypt’s Temple

of Luxor, publishing the book The Temple of Man, pursuing

the link between the cosmic and terrestrial realms, and focusing

on alchemy, physics, mathematics, sacred geometry, art, astronomy,

and symbolism.

6. Here, Christofides refers to Paul Klee’s ‘magic squares’

paintings, for example Ancient Sound, Abstract on Black;

Harmony in Blue and Orange; Abstract Colour Harmony.

Many were painted in the 1920s, with their rhythmic chromatic relationships

expressive of polyphony.

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Photo

credits: Jennifer Leahy, silversalt photography, 2010, unless otherwise

attributed

Andrew Christofides' images courtesy of the artist and King St Gallery

on William, Sydney, © Andrew Christofides

© Kurt Schranzer 2011 |

|