|

|

|||

| |

|||

|

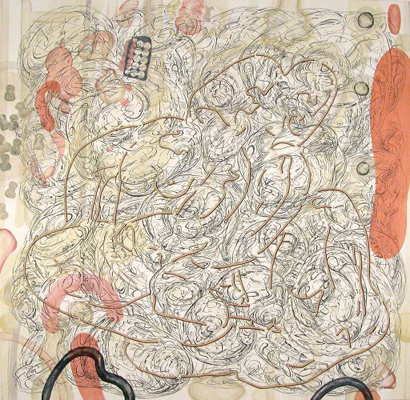

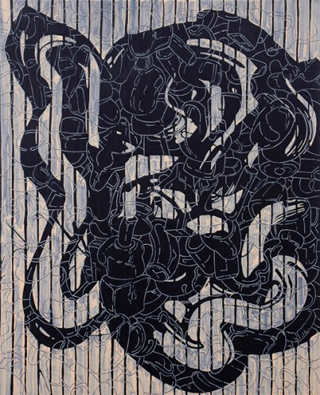

Terry Burrows 2003 01, acrylic on canvas, 180 x 180 cm |

||

|

|||

The interconnectedness of, and the struggles and tensions between <<Spirit & Flesh>> have been canvassed by writers, artists, mythologists, philosophers both past and present. Kurt Schranzer & Terry Burrows: Spirit & Flesh brings together selected artworks under this overarching theme, moving beyond the Western-centric Christian narratives that are usually associated with the phrase (the battle-loaded oppositions of purity of spirit and worldly, carnal nature), to yield more varied, absorbing, profound forms and meanings. The theme is expressed through the separation and ‘oneness’ of spirit and flesh, the cosmic and the earthly, the psychic and physical, the metaphysical and scientific. Evident is the fragmentation, reconciliation, and integration of the body divine with the psycho-sexual and mechanical body; delusion and illusion alongside reality and materiality, formlessness against form, transition with permanence; aspects of creation, holism, embodiment, awakening, ascension, and suspension. Also framed are the singular, dualistic and pluralistic natures of humanity and self; connection and disconnection; isolation and interaction; physical, cultural, and spiritual communication and union with the ‘other’. |

|||

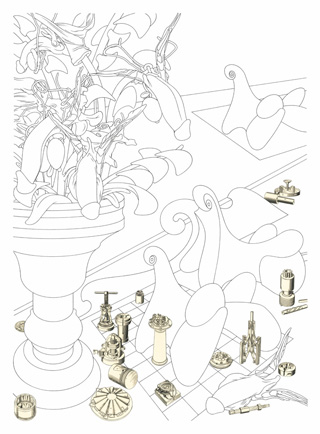

Kurt Schranzer Metaphysisches Stilleben (The Garden of Earthly Delights) 2010, diptych, ink and collage on paper, each panel 76 x 56 cm |

|||

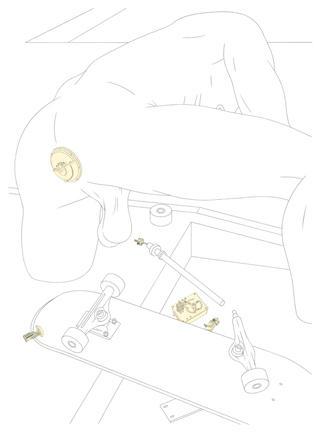

Kurt Schranzer, Fallen Skateboarder 2006, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm |

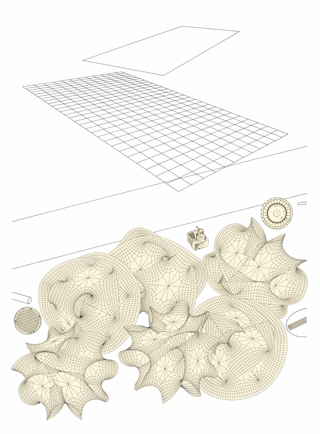

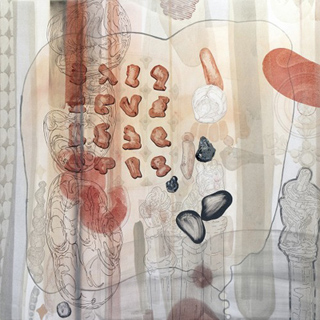

To introduce the paradigms of <<Spirit & Flesh>> within Kurt Schranzer’s drawings is to note, firstly, that their visual restraint and creative sophistication is wedded to their coded psychoanalytic content and his introspective mythologies. They are imaginative and individualistic, yet presented in tableaux aligned to the pictorial and metaphoric traditions of Surrealism and Metaphysical painting (with objects, organisms, bodies, and body parts arranged in new relationships and composite forms — removed from the ordinary world “pointing to a higher, more hidden” and complex state of physical, inner- and inter-dimensional being, to paraphrase Carlo Carrà).[1] His diverse forms, themes, and myriad sub-themes are taken from the biological and physical sciences, art history, literature and poetry and are surely — and I would posit largely — autobiographical in nature. These psychoanalytically fertile drawings — viewed as a whole, and adopting a Jungian perspective — are illustrative of his personal consciousness of motif and content as he explores themes of ‘self’ and ‘the nature of being’, tethered to a personal unconsciousness of meaning and a collective unconscious whose archetypes are common and inherited. His drawings, too, are like a Freudian defensive activity, managing both his physical and cosmological anxieties, impulses, responses, positions, and questions; this through their intellectualisation, sublimation, sexualisation or desexualisation, their abstraction (conceptual but also visual), aestheticism and asceticism and correspondingly their control, repression, inhibition, depersonalisation, detachment, rigidity of mark and line, using “templates, a ruler or a compass,” even isolation and “withdrawal of affect, which can be seen in… [his] monochromatic drawings… and forms that are not filled in with colour or shading.” They are a “compromise between the drive derivatives and [his] defenses used to manage them”[2] as he navigates his world and explores issues of sexuality <<Flesh>> and Pandeistic philosophy <<Spirit>>. As examples, drawings from Schranzer’s Le cul mécanique series reveal “sexual archetypes, athletic provocateurs, and ‘differently-figured’ transgressive outsiders” in the guise of skateboarders, while more recent drawings reveal his interest in quantum theory and the philosophical implications of quantum reality. Of the former, his youths are more than just fleshy and mechanical “conduits and… sexual apertures.” They offer up “visual ruminations on the ‘self’ — both the physical and psychic — of the ‘other’ — and of broader human conditions… the physical world and all its modern paradigms, nature, humanity, and spirituality.”[3] In the latter case, he adopts the calabi-yau forms of Super-String theory (the extra 6 space dimensions considered to be a part of nature, so rolled up, so small they are unobservable by the human eye) as a metaphoric vehicle to explore paradigms of connectivity, consciousness, and wholeness, in mind, body, and spirit. In Metaphysisches Stilleben (The Fabric of the Universe), 2010, these calabi-yau manifolds, alongside spatial grids, are used as a metaphor for ‘god’ and spiritual integration. Schranzer speaks of Pandeism and the book God’s Debris (Scott Adams, 2001) as holding that the universe is identical to God, and that as God annihilated itself in the Big Bang — becoming the universe to experience its own ‘being’ — it became unconscious and non-sentient. God became the smallest units of matter, time, space, gravity, and is slowly reassembling itself, growing towards consciousness of ‘self’ through humanity. The potential for consciousness “should be intrinsic to all matter and energy, in all space and time dimensions.”[4] No doubt, like mandalas (alongside other archetypal abstract forms that spin or spiral, are circular or elliptical), the calabi-yau form might allow the artist (and the viewer) to become “inwardly aware [of the universe and] of the deity. Through contemplation, he recognizes himself as God again, and thus returns from the illusion of individual existence [and self-deception] into the universal totality of the divine state."[5] These are the complex narratives and polarities that <<Spirit & Flesh>> presents for the viewer, and the reader is fortunate that Schranzer alludes to this complexity in various published and unpublished artist’s statements. |

||

Kurt Schranzer Metaphysisches Stilleben (The Fabric of the Universe) 2010, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm |

|||

|

|||

Kurt Schranzer Island of the Dead (The Birds are Dying in Their Aviary) 2010, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm |

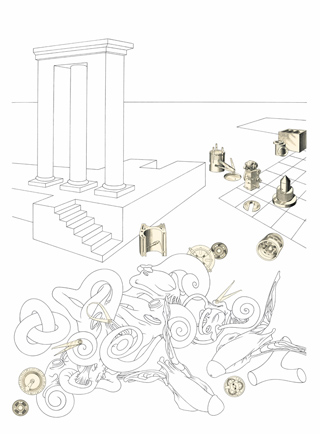

In the drawing Metaphysisches Stilleben (Nights so Dark They Festered Stars), the calabi-yau stars of the title “signify a lattice of connectivity and the "Divine Lila" (Play or Game of Life).” The stars also have darker connotations: they fester and “suggest a difficult, inflammatory incarnation, a blockage of ‘the physical self’.” The narrative is supported by a flayed, anatomical penis — the male laid bare and vulnerable — alongside a small glass slipper refering to the Cinderella folkstory and its psychosexual elements of isolation, oppression, and neglect.[6] In Metaphysical Still-Life with Caped Bat-Figure and Decaying Self-Portrait (The Arrival of the Oversoul), an “angelic bat-figure descends with the Oversoul” (for Ralph Waldo Emerson the term denotes a supreme underlying unity which transcends duality or plurality, much in keeping with the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta,[7] though the title can also be seen as a reference to Oversoul Seven, a non-physical personality who is trying to understand the nature of being).[8] Together they survey “the anatomical and ‘gross differentiated body’, the decaying remnants of an individual’s ego, impressions acquired over the course of evolution and reincarnation.”[9] Island of the Dead (The Birds are Dying in Their Aviary) makes references to 16th–18th century allegorical painting and Surrealism to tap into a tradition that links the bird with the penis, power, sexuality, and loss of innocence. “The bird is a phallic symbol par excellence, and these birds are dysfunctional amalgams of ocean debris, inner ears, and mechanical calipers, questioning masculinity, self-identity, and spiritual and erotic freedom.”[10] A Horse, A Horse, My Kingdom for a Horse brings sexualized, fleshy flowers (reminiscent of Strelitzia reginae) into contact with a tilted ground plane of horses (symbolic of the knight and his transformational role, sexual and romantic impulses and possibilities), as well as a chessboard and its uniquely machined pieces. These chess pieces are, according to Schranzer, one of many recent references to Herman Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game (Das Glasperlenspiel, 1943, also published under the title Magister Ludi, the “master of the game”), which makes mention of chess and mathematics: “chess games in which the pieces and squares had secret meanings in addition to their usual functions.” The Glass Bead Game is supposed to integrate all fields of human and cosmic knowledge, and as Hesse writes, leave the player with the feeling “that he has extracted from the universe of accident and confusion a totally symmetrical and harmonious cosmos, and absorbed it into himself.”[11] |

||

Kurt Schranzer, Metaphysisches Stilleben (A Horse, A Horse, My Kingdom for a Horse) 2010, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm |

Kurt Schranzer The Glass Bead Game (The Debris of Creation) 2010, ink and collage on paper, 76 x 56 cm |

||

Thus, references to <<Spirit & Flesh>> are steadily garnered — pictorially, symbolically, by way of title — in individual drawings and thematically across artworks. Drawings with immediate erotic readings and an overt sexualization of subjects (and correlatively, we might assume, the artist’s agency and urgency of sexual expression and objectification) may be challenging for the viewer. The fact, however, that Schranzer’s many references and meanings are often veiled and layered, requiring from the viewer a sophisticated literary, philsophical, subcultural and psychoanalytic entry point, is testament to their depth. It is also in those allusions that they function most deeply, richly, compellingly, and are vastly more challenging. |

|||

|

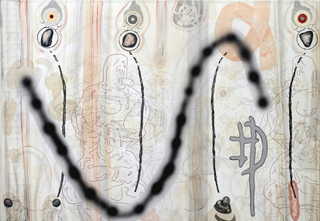

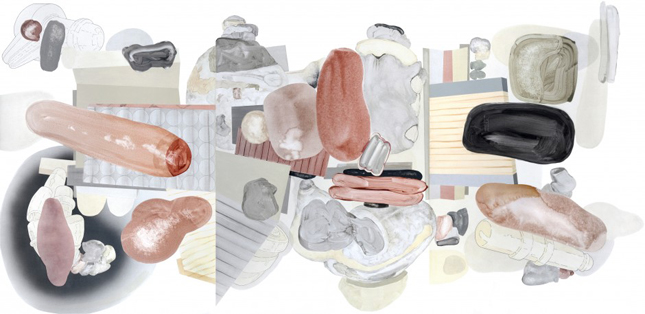

The artworks of Terry Burrows hint at Twentieth Century biomorphic surrealist painting, Philip Guston’s quasi-representational paintings from the 1970s, and fellow contemporary Australian artists such as Brent Harris. Colours and forms both etheric and fleshy, even visceral, inhabit his compositions; there are glazed soft pinks, blood reds, smokey greys, creams — the colours of offal — muted pastels, tertiary blues, asparagus and laurel greens, and calligraphic black on white. There is much ambiguity of nature and physical state: objects defy or blur categorisation; Ann Finegan calls this “the objecthood of some unnamed thing.”[12] They are formed yet formless, animate and inanimate, microbial, vegetal, culinary, anatomical and humanoid. Even when planar and architectural elements are introduced and interact alongside the organic, they collide and assemble themselves in an ambiguous, polypous, metaphysical-scape. There are suites of Burrows’ works that appear to be highly pictographic, scientifically coded and symbolic of galaxies, nebulae, cosmological and etheric phenomena; yet the viewer is also taken on a journey inwards into the chromosomal world, with what appear to be genes and other nucleotide sequences, eukaryotic cells and prokaryotic cells, all in a nod to the earthly and physical. Burrows appears happy for multiple readings of his shapes, substances, and objects, especially as he leaves his paintings ‘untitled’ and hence open for interpretation.

|

Terry Burrows, 2007 04, acrylic on canvas, 137 x 137 cm |

||

Terry Burrows, 2007 03, acrylic on canvas, 3 panels, 105 x 360 cm |

|||

Terry Burrows 2005 01, acrylic on canvas, 86 x 70 cm  Terry Burrows Terry Burrows2004 05, acrylic on canvas, 137 x 198 cm  Terry Burrows 2007 07, acrylic on canvas, 167 x 213 cm |

In some paintings an orgy of semi figurative and abstract, amputated jelly-like figures, body parts, limbs, phalluses, circular and kidney shaped organs are penetrative and receptive, active and passive. I see them seeking, soliciting, lolling, floating, bumping, clutching, fused and wedded — in both physical and spiritual communication. Sometimes open mouthed figures wait expectantly for communion; seeking “fellowship” (κοινωνία) and “sharing in common” (communio) as the Greekand Latin roots suggest; accepting spirit, the Host, if we interpret it thus; or more basely, desirous of oral gratification and sexual fulfillment. Indeed, in paintings like #5 2004, there are mouths both receptive and filled, the latter with a mutable, protean phallus; a Lingam; or a column, the mythological Stambha, the cosmic shaft that bonds the heaven and the earth.[13] Burrows makes specific reference to the Lingam in an unpublished artist’s statement (2011): “#7 2007… refers directly to the figure and its association with objects,” the latter having “playful phallic connotations” informed by “the Shiva Linga (the symbol of regeneration associated with the Lord Shiva). In this painting the figures are attempting communication with each other via these objects, or morphing with the objects, creating a hybrid of sorts….” Complexly, as Burrows suggests, the figures are both ‘separate from’ and ‘merged with’ these cylinder-come-pillars; they are synthetic, iconic representations of deity and man (perhaps Burrows, the man himself), and are clearly suggestive of the many sculptural variations of the devotional, aniconic Lingam; the pillar is the phallus, the phallus is conjoined with the female organ, sculpted as a receptacle. Burrows illuminates, quite unknowing of the implications, that some of his “earliest references to the objects in mouths were 'word as object' rather than as phalluses,” that they alluded to an “impotence with words,” and “even earlier works had an unbroken tube between character’s mouths, sometimes coming from one’s mouth into another's anus passing all the way through the body out of the mouth again…..and on and on. The great continuum, the snake eating its tail….”[14] Further, he mentions that in these communications, “sometimes they’re… successful and they’re locked together, sometimes they’re not… the shapes tend to be the baggage or detritus that’s thrown out of those processes of communication."[15] When Burrows speaks of a kind of impotency or blockage with words, he is also suggesting, concomitantly, that he (and his figurines) heralds a desire for the opposite: a spiritual and physical potency; a voice, an intimacy, a knowledge that is open, unobstructed, free-flowing. Of course, it is a communion and transmission, a giving of words and wisdom that cannot be separated from the phallus (and his phallic symbols). Though the word and its meanings might be foreign to Burrows, I cannot help but think of Areté (Greek: ἀρετή), a term linked with human knowledge and virtue, with a set of significant human abilities or values derived from it: honour, courage, strength, effectiveness, fairness, and honesty. Areté was “held to be physically transmissable… A man’s semen was held to be the carrier of his areté which was physically transferred through the act of love under proper cultic circumstances involving the consent of the gods.”[16] As such, sex, and the phallus, served as a medium for initiations into learning. Burrows’ figures and phalluses might then be ritualistic, totemic, spiritually significant, and holders of and impregnators of earthly virtues. There is a great layering of meaning — or potential meaning — and a complexity that speaks of the mystical and the physical, of self and culture. John Comonos writes of Burrows having the idiosyncratic vision of someone who weaves his compelling, semi-figurative images into “expression[s] of dialogue, intrigue, play, touch and sex… derive[d] from both Western and Asian art, culture and philosophy….” They are often “indebted to the traditional ideas of Hindu Tantric and Buddhist art,”[17] both sculpture and architecture. Burrows’ interest in Hindu temples began on his first trip to India in 2005, visiting “Khajuraho in Northern India to see the erotic sculpture of the Chandella era temples.” Interestingly for Burrows, the earlier name for Khajuraho was Kharjuravahaka; ‘vahaka’ being a sanskrit word for “one who carries,” for themes of ‘sex’ and ‘carrying’ played a major part in Burrows earlier works.[18] |

||

Terry Burrows, 2009 02, acrylic on canvas, 150 x 150cm |

Terry Burrows, 2009 03, acrylic on canvas, 180 x 240cm |

||

#2 2009 was produced on a later trip to South East Asia visiting Hindu and Buddhist temple complexes. Though places of past or present worship, they are often in decline: one thinks of the Bagan monuments in Burma where “Buddhist temples, monasteries and stupas have been speculatively rebuilt from mounds of rubble since 1995”[19] due to weather and earthquake damage, or back to the subcontinent, where “Ancient Hindu temples in a ruined or semi-ruined state can be found forsaken all over India… simply abandoned for decades to water and wild vegetation, cattle and wild birds…. [perishing] at the hands of Muslim iconoclasts and plunderers, Indian and British robbers of art and antiquities, [and] raided by sculpture thieves and damaged by vandals…. Precious temples have been silently disintegrating into piles of stone blocks.”[20] For Burrows, these “pieces of stone that are recognizable details from sculptures, or… stone slabs that were part of the foundations… still retain the spirit of the original.” Thus, the decayed temple or pile of ruins — degraded, deconstructed, and transformed — is still an artefact and shrine, and his painting — with its piled conglomerate of shapes emblematic of both physical and sacred presences — is a holy stand-in for it, providing an avenue, mechanism or channel for further metaphysical reflection or spiritual devotion. In this sense, Burrows is like a Burmese Buddhist who believes that “restoring a temple doesn’t mean so much restoring it to how it originally looked as enabling it to become a place of worship again.”[21] Of course, as Burrows points out, this pile of temple ‘rubble’ is also a “pile of clothes or bedding, dishes stacked up on the kitchen sink, a coupling couple, a figure laden with clothing”[22] — scrap-metal-cars with their fenders, grilles, and body panels crushed — a cancerous growth or sessile polyps seen by endoscope — a Neo-Florentine tondo of Madonna and Child — for his forms are not only ambiguous but are animated by a supernatural power that organizes the material universe out of any available object or subject, and then transmutes it at whim. In the fiction of shifting iconographies, in the frisson emitted between the abstract and the figurative, the known and the unknown, the spoken and the unspoken, Burrows is an arcane master. |

|||

Terry Burrows, 2008 01, acrylic on canvas, 3 panels, 145 x 300cm |

|||

<<Spirit and Flesh>>… two sides of an ever spinning coin; different sides of the same coin, but still the one coin. In a sense, it is within this matrix of the esoteric and the physical — the celestial and the earthly — that “everything is all-meaningful”: within all elements of the pictorial whole of Schranzer’s and Burrow’s works, and in “every symbol and combination of symbols,” one is “led not hither and yon… but into the center, the mystery and innermost heart of the world,” into self knowledge. “Every… artistic formulation [is] nothing but a direct route into the interior of the cosmic mystery.”[23] Moses Langtree Hulme, Lancashire, January 2013 |

|||

|

|||

NOTES 1. This sentence itself paraphrased from Metaphysische Stilleben, exhibition press release, Flinders Street Gallery, April 2011. Though Carrà is known for his futurist paintings c1910, after meeting de Chirico he worked for a brief period c1917 in the style of pittura metafisica. 2. The defenses, defense mechanisms, and heirarchical complexities in children’s drawings are noted in Daniel Benveniste, “Recognizing Defenses in the Drawings and Play of Children in Therapy,” Psychoanalytic Psychology, Volume 22, Number 3, Summer 2005. These psychological drives and defenses — healthily adaptive or immature, even pathological — must also be tied to the artistic processes and visual expressions of the mature, creative individual who seeks to cope with reality and maintain his or her self-image intact. 3. Moses Langtree, ‘Le cul mécanique’, 2006, in Le cul mécanique, exhibition catalogue, published by Kurt Schranzer, 2006, Queensland. 4. Kurt Schranzer, unpublished Artist’s Statement for Blake Prize for Religious Art, 2011. 5. Carl Jung, ‘Concerning Mandala Symbolism’, translated from ‘Uber Mandalasymbolik’ in Gestaltungen des Unbewussten, Rascher, Zurich 1950, p73. 6. Kurt Schranzer, artist’s statement in Adelaide Perry Prize for Drawing 2011, exhibition catalogue, Adelaide Perry Gallery, The Croydon Centre for Art, Design & Technology, PLC, Sydney, February 2011. 7. Advaita Vedanta is a sub-school of the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy. Advaita (literally, non-duality) is a system of thought refering to the identity of the Self (Atman) and the Whole (Brahman). 8. See: Jane Roberts, The Oversoul Seven trilogy: The Education of Oversoul Seven (1973), The Further Education of Oversoul Seven (1979), and Oversoul Seven and the Museum of Time (1984). 9. Kurt Schranzer, unpublished artist’s statement for Blake Prize for Religious Art, 2011. 10. Kurt Schranzer, unpublished artist’s statement for Duke Art Prize, 2010. 11. Peter Higbie van Ness, Spirituality, Diversion, and Decadence: The Contemporay Predicament, 1992, State University of New York Press, Albany, p255. 12. Ann Finegan, Terry Burrows: A Short History of Large Works, exhibition essay, SCA Galleries, Sydney College of the Arts, The University of Sydney, March-April 2006. 13. The Lingam, or Linga, is a representation of the Hindu deity Shiva, a symbol of the active, male creative energy. In close association with the Lingam, the Stambha (or Skambha) is believed to be an endless cosmic column, a pillar of fire, that joins the heaven and the earth. (Swami Vivekananda, "The Paris Congress of the History of Religions" in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Vol.4.) 14. Terry Burrows, email correspondence with Kurt Schranzer, Re: newcastle show, 3 December 2011. 15. Louise Maral, ‘Terry Burrows' history of his own works’, The University of Sydney, News, 17 March 2006. http://sydney.edu.au/news/84.html?newsstoryid=954 16. Horst Hutter, Politics as Friendship, 1978, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, p.79. Areté is often spoken of in relation to Greek paederasty — the transmission of virtue between an older and younger male through sex — but is used here with no gender overlay. 17. John Comonos, June 2004, Terry Burrows: Now & Then, exhibition essay, FCA Gallery, University of Wollongong, August 2004. 18. Terry Burrows, unpublished artist’s statement on the painting #2 2009 and early trips to India, 2011. 19. Bob Hudson, ‘Restoration and reconstruction of monuments at Bagan (Pagan), Myanmar (Burma), 1995–2008’, World Archaeology, Volume 40, Issue 4, 2008, pp553–571. 20. Rizwan Salim, ‘Neglect and decay of ancient temples’, Hindustan Times, July 21, 1996. [Italics mine.] http://www.hindunet.org/srh_home/1996_7/msg00364.html 21. Bob Hudson, op. cit. 22. Terry Burrows, op. cit. 23. Here, one takes liberties with the words of Hermann Hesse, The Glass Bead Game, as quoted in The Glass Bead Game: Cosmic Play in a Symbolic Universe, http://www.glassbeadgame.com/ |

|||

|

|

|||

|

NOTE: Due to the low resolution of computer screens, the lines

of these drawings will present as slightly pixelated. A 'jagged'

quality will be particularly evident on some diagonals and curves;

fine black ink lines will appear faint and tend towards grey on

screen. |

|||